A lot of the—and I can't believe I need to use this term, but there really is no other way to phrase it—critics of privacy have this tendency to see privacy only through the lens of 'threat'. As the threat has built and they can’t reconcile their self-image with popular and consistent interest in privacy regulation, things have taken a turn. There's always a plot, a secret agenda, a behind the scenes manipulator. At this point I am used to being called “boring”, an “absolutist”, or a fundamentalist, but now it’s escalated to “extremist”. In the latest volley, the privacy movement has been accused of being orchestrated by “Dark Money”. Accountable Tech is called “virulent”. Critics are “inflammatory”. It is easy to see ad tech’s industry leaders drawing up their lines opposing privacy. This ad tech position is just wrong. It is a lie. It’s dangerous to their own constituents and in opposition to the citizenry of nations all over the world who have been calling out, in one form or another, for privacy laws applied to an industry that has failed to do even the smallest amount of self-regulation.

This position has been publicly constructed in front of us by those who fear the changes privacy might bring: ad tech is positioned as reasonable compromisers helping the little guy; while they accuse ’elites’, ‘academics’, and ‘dirty money’ of trying to create a fantasy movement for privacy while ad tech leaders claim none truly exists. For the defenders of personalized tracking, it isn’t just ‘small businesses’ any more, ad tech wants to position itself as an angry populist movement, because that is the new standard procedure for subverting actual movements with broad national support, of which privacy is one. The great middlemen extractors of the ad tech industry want to claim that they represent the open web. They don’t. They only feed off it. Privacy on the other hand is an actual popular movement with real citizen support and a long history at the heart of the internet.

So much of this opposition to privacy by ad tech seems to come from a much more boring place. Many have become rich and comfortable profiting off of the unregulated trade of user data. Many of these people don't even run well-functioning companies. The big black box of ad tech has allowed many operators to become rich, build big profits, but also be lazy. When everyone is talking about measurement and allegedly no two measurements give the same results there is no such thing as measurement.

Ad tech firms can easily perpetuate fraud against advertisers and publishers. Even when ad tech middlemen don’t perpetuate fraud, the anti-privacy stance defends a model that allows ad tech to profit by observing users at high value sites and arbitraging their purchase on low value sites, sometimes hate sites, sometimes fraud sites, sometimes sites under international sanctions, but also just bad sites. The black box is an intentional design that allows them to extract even more value from every participant in the ecosystem, while simultaneously funneling money to the web’s worst actors.

Ad tech leaders who make their money in the foggy middle of the ecosystem are lazy because there is currently almost no way to catch them being incredibly bad at their job and making a tremendous profit off of it.

The middlemen are flying high, taking a cut of the ad tech tax, and desperately afraid that even the smallest amount of regulation might reveal the majority of the more than 10k ad tech companies are built on top of extremely unstable sand. So the big opposition comes from the place most Big Opposition comes from: fear of change.

Let me be blunt and clear with you about what I don't dispute: That fear is legitimate. Privacy will disrupt the ad industry significantly. The narrowing of signals will mean measurement will be forced to become more accurate or not work at all and there will be far fewer measurement companies needed. The end of cross-domain trade in real-time user-data-as-currency will negate the need for what is likely to be thousands of jobs.

The reshaping of the programmatic landscape will leave hundreds of parasitic lamprey ad tech firms with no leg to stand on and no actually functioning technology to fall back on.

I'm not going to, nor have I ever, lied about this.

But also, it doesn't have to end with thousands of jobs lost--if leadership steers the boat away from the gaping whirlpool that is opening up immediately in front of it.

Most ad technology in the modern age is built on top of a fundamentally unethical system and it leverages that unethical system to build palaces of fraud, monopoly, bad practice, inaccuracy, rent-seeking, and tax. To build these palaces the systems of modern ad tech infringe on our human rights. I'm not making up a all-new right here, I'm quoting one:

Article 12

No one shall be subjected to arbitrary interference with his privacy, family, home or correspondence, nor to attacks upon his honour and reputation. Everyone has the right to the protection of the law against such interference or attacks.

From: the UN Universal Deceleration of Human Rights.

This is where things get messy, because what the Anti-Privacy Opposition doesn't understand is that the movement towards privacy is a people's movement and more than that it is a human rights movement.

The type of opposition that puts you at odds with a legitimate human rights movement isn't just about who gets to preserve capital and when. It's about who is on the right... and wrong... side of history.

So let's talk about history.

Fairy Tale History vs Real World Action

In "Fairy Tale History: The Root Of America's Problems" journalist Oliver Willis explains how the United States has failed to teach history:

Via laziness and repetition, combined with outside forces that have shaped education curricula, we collectively learn a fairy tale. While it is understandable that young children aren’t exposed to the horrors of chattel slavery in their kindergarten classes, or told about the subordinate role women were forced into in America’s early days, or how Native Americans were systematically killed and had their lands stolen from them, it is a failure that these topics aren’t as familiar as the founding myths.

All countries have their shared national origins, but in America it tends to resemble something like a Marvel Comics-level myth.

I think this is 100% true and Willis focuses on how we have erased the violence of discrimination, slavery, and the unequal application of human rights from our history. We need to fight the myths of bad history because if we do not, the sins we wish to ignore from our history will inevitably come back in an acid reflux burn to the state and society.

That is not the only thing we have erased from history. We have also erased the consequences to the opponents of human rights. When we falsely perceive that slavery was solved with the Gettysburg Address; that civil rights were solved by one MLK Jr. speech; that women's suffrage was solved by an amendment; that Roe v Wade ended the question of abortion rights with swift correct justice; we don't just erase the history of the worst things our society has done and still benefits from today, we also hide the direct and violent actions that underlie the progress that was made.

In Andreas Malm's How to Blow Up a Pipeline the Swedish climate scholar explores the strange re-framing of history that the climate movement has engaged in to justify a mandate for non-violence and the problems of this pure non-violent approach.

Malm notes:

The commitment to the endless accumulation of capital wins out every time. After the past three decades, there can be no doubt that the ruling classes are constitutionally incapable of responding to the catastrophe in any other way than by expediting it; of their own accord, under their inner compulsion, they can do nothing but burn their way to the end.

Yet in the face of these vampire capitalists the environmental movement only summons non-violence, and it rewrites history to make this choice appear continuous with history. But Malm provides counter arguments:

collective action against slavery perforce took on the character of violent resistance.

and

The suffragettes took great pains to avoid injuring people. But they considered the situation urgent enough to justify incendiarism – votes for women, Pankhurst explained, were of such pressing importance that ‘we had to discredit the Government and Parliament in the eyes of the world; we had to spoil English sports, hurt businesses, destroy valuable property, demoralise the world of society, shame the churches, upset the whole orderly conduct of life’.

among other examples.

The conclusion he gets to is quite clear in his analysis of the American civil rights movement:

The civil rights movement won the Act of 1964 because it had a radical flank that made it appear as a lesser evil in the eyes of state power.

You should read the book, I highly recommend it, especially since I am grossly simplifying its argument here.

To reinforce his conclusion, Malm notes that environmental justice is uniquely well situated for direct violent action against property as part of protest because to do violence against polluting property is to not just show willingness to take protest to its most extreme conclusion, but also serves the function of environmentalism by eliminating a thing that is doing polluting.

Malm paints the other missing side of history, we can't just teach the terrible things we did in our history; we must also recall the terrible things those who fought for human rights did to defend themselves and bring their cause to realization.

I am not calling for violence, that is the sort of thing that gets one in trouble, but I couldn't help but think that many of the arguments Malm makes about environmental action are just as applicable to the cause of privacy. His portrayal of the insane suicidal opponents of environmentalism feel akin to how the anti-privacy leaders act.

Ad Blockers are Direct Action

I think it is actually a really easy argument to make that Ad Blockers are a sort of intentional vandalism of the web. They deface websites in a pretty direct way. Imagine if you went to your local newsstand and took the entire stack of newspapers, cut every ad out of them, and put them back into the stack. There would be no argument about what this was.

When I call ad blockers vandalism though, it isn't a criticism. It is a recognition that the people want privacy and have already begun to leverage violence against property to get it, even if not every individual can fully articulate it that way. The future of protest is the past here and it turns out the longest running and most expensive example of political industrial sabotage has been here, running in browser extensions under our noses all along.

The IAB’s demonization of ad blockers shows just how deep the threat of its stance against privacy could be to publishers. It has created an opportunity for the ad blocker, like some past direct action campaigns, to be infiltrated and subverted by its target—the ad blockers that are easiest to find in a search are those that participate in an “Acceptable Ads” scheme which allows privacy-violating trackers.

We need to recognize that while we might have erased our perception of history, as Malm notes, direct action against the suppression of human rights is a historical constant.

While Ad Blockers are easy action by people, the less easy action (one less easy to subvert as well) seems inevitable if the powers behind the ad tech lobby continue to try and suppress, denigrate, and ignore the privacy movement.

Many of the arguments Malm makes in his book about the justifications & logic of doing physical violence to the mechanisms of pollution apply just as well to so much of ad tech's mechanisms of tracking and user data.

Asymmetry invites action

In "Principled Privacy" Robin Berjon talks to the misuse of user data and the power differential they create:

These asymmetries of power need to be addressed. They threaten personal autonomy, they harm innovation and economic diversity, and they damage collective intelligence

Asymmetries of power are vulnerable to action by the people and they push citizens into positions where they feel they have nothing to lose. Running Privacy Badger or Orion to block network signals is just the simplest example. Let us follow through: take a look at a Digital Billboard, like LinkNYC, as a mechanism of realizing the asymmetry of personalized cross-context cross-domain tracking into the physical world. This device runs ads and these ads are increased in value through tracking, perhaps in the device itself, but likely much more simply through the purchase of user data from cell phone providers.

Attacking and defacing or destroying digital billboards has almost no downsides from an activist perspective. It seems easy. No chance of hurting a human. It doesn't have the immediate surveillance of attacking a camera. It serves both as protest message and direct action against the problem because it makes using personalized advertising techniques directly less profitable.

Now I'm not recommending you take a hammer to your nearest digital billboard. In the same way that I think How To Blow Up a Pipeline is an interesting and useful thought experiment that can lead you to draw real conclusions I wonder if this concept--what would it mean and do to destroy a digital billboard in the subway or on the street--is also useful. It brings the concept of running an ad blocker into a more physical reality.

Beyond that, I wonder if it is predicting the inevitable. There are so many products out there in the physical world and on store shelves that are vulnerable to exactly this type of destructive action.

If the argument to regain the human right of privacy is frustrated by the entities that represent ad tech middlemen in DC I wonder if direct action will inevitably escalate to the point that the physical mechanisms of ad tech become common targets. I wonder what new ways digital property destruction will come to be realized beyond ad blockers. Especially if they can’t shake the energy and material use that links these concerns with environmental ones.

What if we just didn't?

I think there is an irony in that none of this has to play out this way. The regime of personalized multi-party tracked surveillance-based advertising has been an extractive one for participants on both ends of the equasion. Buyers pay more yet commonly report that most digital advertising does not deliver outcomes, when it is not outright harmful. Users deal with a worse, heavier, and offensively invasive web and increasingly decamp to more and more limited walled garden platforms. At the same time the asymmetries of power are exacerbated by privacy-invasive ad tech. Most publishers have been in an endless downward spiral. Those problems will only be worsened by ad tech firms forcing users to manage increasingly complex consent systems that users will more and more often use to say no to tracking with.

All the money that goes into ads and all the legitimate supply that provides an outlet for those ads are ill-served by the status quo.

The only ones who are truly making out like bandits are the middlemen, the tax collectors, the data traders who have convinced the world that they need to exist.

...

They don't need to exist.

...

If we acknowledge that, then no one need lose their job. The move to privacy provides many business opportunities in and of itself. A private world will require new technologies, interesting products, and new approaches. A technological revolution approaches the horizon and that is a wave that the firms threatened by privacy could ride, instead of be drowned by.

But the rhetoric of the leaders of ad tech would push you under that wave. It pushes ad tech into an eternal war with users, a never ending opposition to not just the very users that you depend on, but to a cause that is tied up inexorably with human rights.

Going to war with users benefits no one but big tech companies who this psychological violence drives users into the walled gardens of; and the ad tech parasites who extract capital from the conflict, mostly by selling the equivalent of weapons.

If ad tech leadership decides to take the position that the only people calling for privacy are extremists then extremists is what they will create.

In the ad tech arms race take advice from an elder AI: "The only winning move is not to play."

Sacred Ground

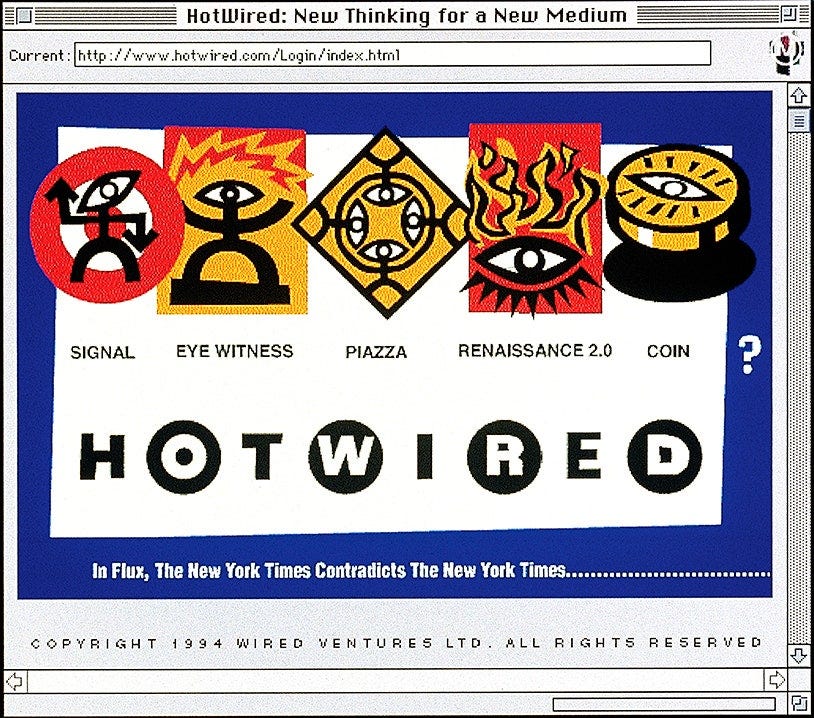

At the beginning of David Cohen's speech to the IAB leadership on this topic he tells the story of the first banner ad ever created for the web, on HotWired. It's too bad that he neglects a deeper look into the history of that particular event.

We came with the attitude that this [the internet] was a sacred ground. The rest of advertising had been ruined and dammit, we weren’t going to let that happen this time,”

-Joe McCambley, one of the creators of the first banner ad.

HotWired was an entirely unique entity compared to modern websites. It didn't look or act anything like a modern website. The banner ad on HotWired was designed to be unlike anything that had come before. It wasn't intended to sell you something directly, it was supposed to bring you to a new experience and to feel like something fresh.

As you consider the future of ad tech, it helps to remember the past with clear eyes, instead of a fairy tale history. The banner ad, now one of the most standard advertising formats, was supposed to be something new and unique, something that leveraged and engaged with users' idealism about the internet and curiosity about what the web could be.

If you have made it this far and are still considering which side of history you want to land on for the human rights battle that is privacy, perhaps recall the real history of digital advertising.

It was made by those willing to embrace change, and the power and wonder of an open web.

///

This post represents my **personal** opinion and does not reflect the position of my current, past, or future employers, this platform, or anyone other than me singularly.